By Bruce Klauber

If anyone ever decided to take on the unenviable task of writing a book about the history of American comedy from 1920 to the present, at least one-third of the book would have to be devoted to comedy teams.

Think about it. Olsen and Johnson, who teamed up before 1920, may have been the first “formal” comedy team, followed by Wheeler and Woolsey, the Marx Brothers, Laurel and Hardy, George Burns and Gracie Allen, The Ritz Brothers, The Three Stooges, Abbott and Costello, Martin and Lewis, Mike Nichols and Elaine May, Rowan and Martin, Allen and Rossi, Jack Burns and Avery Schreiber, The Smothers Brothers, Cheech and Chong and others long forgotten.

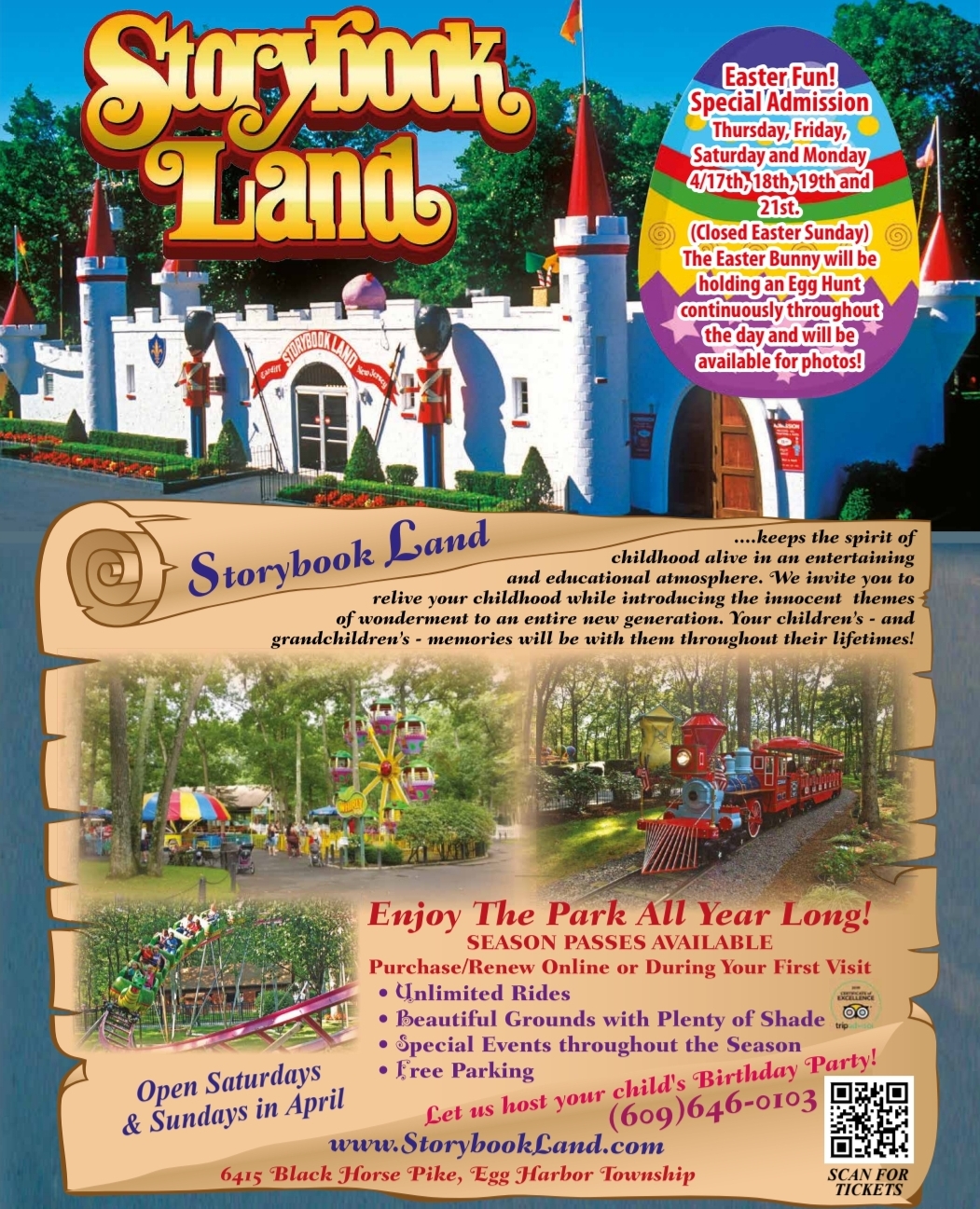

Definitely not forgotten, at least in our area, are South Philadelphia’s beloved and always-hilarious Fisher and Marks, who worked summers at the Jersey Shore – Atlantic City, Wildwood and points in between – since they first started working together around 1948.

As the story goes, Al Fisher and Lou Marks teamed up after Fisher got out of the Navy following World War II, and started singing and dancing in area night spots. In 1948, Fisher was singing at Philadelphia’s famed Palumbo’s nightclub, while Marks was doing a jitterbug act on the same bill. Following in the footsteps of Martin and Lewis, Lou grabbed a tray and a busboy’s apron and began heckling Fisher.

Frank Palumbo loved it, as did the audience. The comedy team of Fisher and Marks was born.

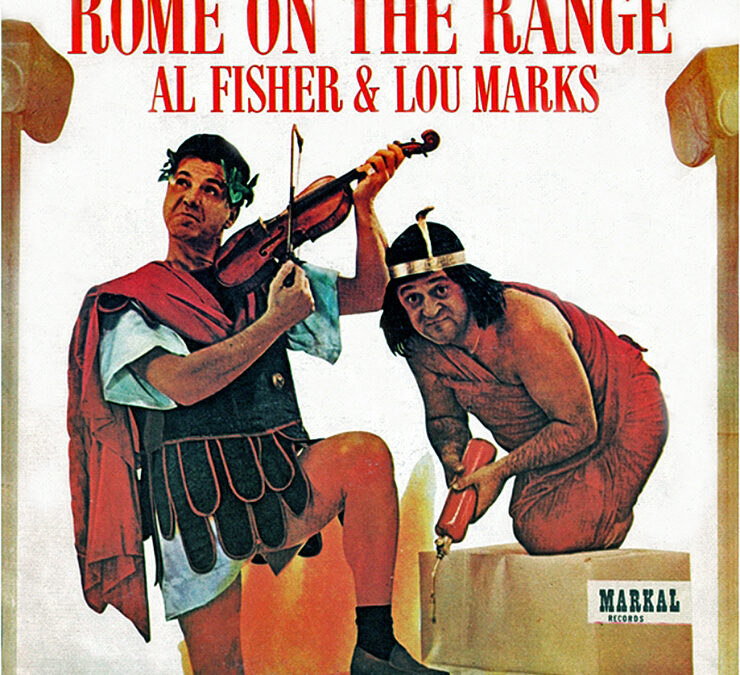

You could say that Fisher and Marks were the poor man’s Martin and Lewis, with a South Philadelphia attitude. But they were much more than that, which accounted for their longevity, popularity and brief turn in the national spotlight.

Fisher was the singing straight man a la Dean Martin, while Marks, wrote The Philadelphia Inquirer, was “runty and bug-eyed with a funny haircut. He was the physical one – one of those natural comics who draws laughs with nothing more than a facial expression or a quirky move.”

Tommy Moore, author and popular comedian in our area, was a major fan for years.

“Everything that is comedy is in their act,” Moore wrote. “Heckling bits, sketches, costumes, props, funny hats, dialects, songs, crazy dances, slapstick, crossovers, blackouts, songs, stories, insults, one-liners. It’s hard to believe that all that can be in one act, but it is. The consequence is simple: standing ovations time after time.”

Based on the team’s immense popularity in Philadelphia and the Jersey Shore, Paramount Pictures signed the team to a five-picture deal around 1957.

They only made two films, both forgettable, low-budget projects geared mainly to the teenage, drive-in crowd. “Mister Rock and Roll” is worthy historically for the filmed appearances of 1950s greats Frankie Lymon, Little Richard, Brook Benton, Chuck Berry and Clyde McPhatter and LaVern Baker. The less said about the follow-up film, “Country Music Holiday,” the better.

How a South Philadelphia comedy team popped up in a film that starred Zsa Zsa Gabor and country music’s Ferlin Husky is anyone’s guess.

Fellow South Philadelphia comedian Joey Bishop promoted them relentlessly, though the national spotlight eluded them after the 1950s. Still, the team was tremendously busy in Las Vegas, in nightspots up and down the East Coast and from time to time, in summer theater. In 1958, they were booked to play a couple of gangsters in “Kiss Me Kate” at the old Camden County Music Fair.

Unlike other comedy teams whose members made it a point not to socialize off-stage, Fisher and Marks were, said Tommy Moore, inseparable. As the story goes, when Al Fisher married singer Lydia O’Connor in 1979, the ceremony was held at Palumbo’s with Judge James Crumlish presiding. When the judge asked Fisher, “Do you take this woman to be your lawful wedded wife?” Lou Marks chimed in, “We does, your Honor!”

Al Fisher suffered his first heart attack in December of 1976, when the team was working in Miami Beach. Noted Philadelphia cardiologist Dr. James Giuffre was flown to Florida to care for him. When he recovered, the team went back on the road and continued on the regular circuit of nightclubs. By the early 1980s, that circuit included Atlantic City’s Showboat, the Trump Plaza and a 1981-to-1983 residency at Atlantic City’s Claridge. By then the team had been in the entertainment spotlight for more than three decades.

Despite the years, Tommy Moore said the team had lost nothing. “The Fisher and Marks revue at the Claridge in Atlantic City is a show you’ve got to see,” wrote Moore. “For my money, Fisher and Marks are the best comedy team in the nation today. If a person had lived in a vacuum all his life and wanted to catch up on all the comedy he missed in one night, I would send him to see Fisher and Marks.”

While working at the Downingtown Inn around 1985, Al Fisher suffered a major heart attack. This time, there was no going back on the road. He retired and passed away a year later.

There was no stopping Lou Marks, however. He continued working with various partners, including the talented and versatile Bobby Burnett, for some years. “Lou makes every night a new experience,” Burnett said at the time.

But it wasn’t the same. Bobby Burnett wasn’t Al Fisher and clubs like the Latin Casino, Palumbo’s and Sciolla’s in Philadelphia were no longer around. And the Wildwood spots where Fisher and Marks “killed ‘em” for decades, were booking rock cover bands. Marks soldiered on, working private affairs and on any stage that would have him.

I played drums for Lou and Bobby Burnett in the early 1980s. Lou was a bit slower and weathered by age, but he was still hilarious and he still “killed ‘em.”

Lou Marks died in September of 2007. He was 87.

Bruce Klauber is the author of four books, an award-winning music journalist, concert and record producer and publicist, producer of the Warner Brothers and Hudson Music “Jazz Legends” film series, and performs both as a drummer and vocalist.