By Bruce Klauber

Hugh Hefner and Atlantic City were made for each other, so it seemed. As the founder of the Playboy empire, Hefner had been selling flesh, flash and glamour since he founded Playboy Magazine in December 1953. Seven years later, he founded the first Playboy Club in Chicago.

The clubs were private, requiring a $25-per-year membership. The first club, which became a template for most that followed, included a Living Room, Playmate Bar, dining room and club room. There was also live, name entertainment, often of the jazz variety.

What made the venue unique is that members and guests were served by the iconic, glamorous, costume-clad young women known as “Playboy Bunnies,” several of whom had been featured in the magazine. The Chicago club must have hit a nerve. By the end of 1961, it became the busiest nightclub in the world, with more than 132,000 visitors.

Hefner would have been foolish not to expand, so expand he did. By the 1980s, there were almost 30 Playboy Clubs operating in the United States. There were also clubs in Jamaica, Montreal, Manila and three in Japan.

Some of the venues were expanded beyond the simple club concept. A few, like the Playboy franchises in Las Vegas and in McAfee – New Jersey’s Great Gorge – were top-of-the-line resorts.

Most were successful. Several, like the locations in St. Petersburg and San Diego, didn’t last long. The idea of a Playboy Club was also proposed for Philadelphia as early as 1968, by Philadelphia entrepreneur and noted bad boy Harry Jay Katz. But the ultra-conservative mayor at the time, James H.J. Tate, and Police Commissioner Frank L. Rizzo, shot it down. Their reasons? A Playboy Club would be “a den of iniquity.”

Hefner entered the legalized gambling fray with legalization of gaming in the United Kingdom in 1965. It’s been said that by 1981, the London club was the most successful casino in the world. A year or two later, two more Playboy casinos opened in the U.K.

Given Playboy’s successful track record in operating clubs, resorts and casinos, it was logical that the next step would be to expand to Atlantic City.

In 1981, Playboy opened a hotel and casino on the Boardwalk along with a partner, the Elsinore Corporation, an outfit that had long and successfully operated the Four Queens Hotel & Casino in downtown Las Vegas. To Hefner’s everlasting credit, he hired a female CEO.

Jeanne Hood, profiled recently in these pages by Chuck Darrow, oversaw the construction of an 800-seat theater, designed by Playboy’s Entertainment VP, Sam Distefano.

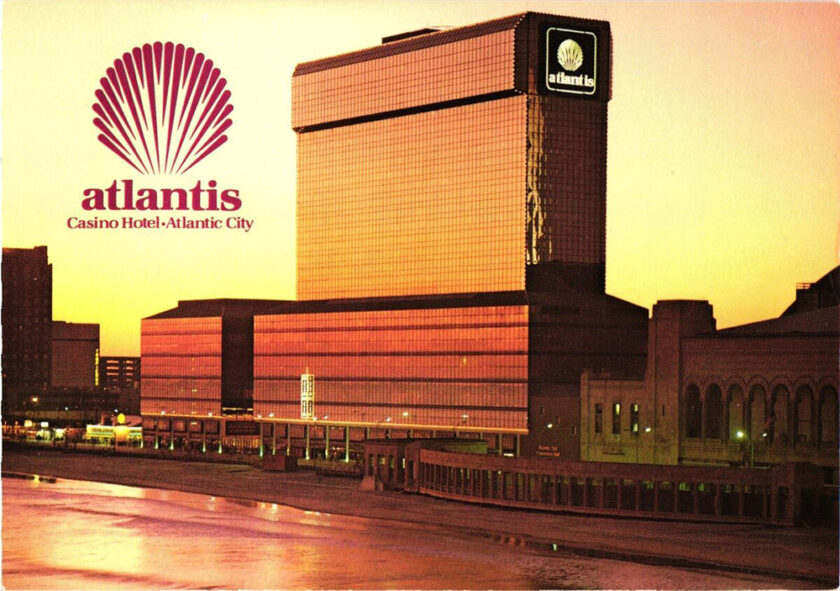

Hood also had to deal with the troubling fact that the property was initially granted a provisional license because the New Jersey Casino Control Commission had issues with Playboy and Elsinore. Specifically, the NJCCC, which was quite strict in the early days of Atlantic City gaming, had concerns about how Playboy obtained its liquor license for its New York City club, as well as the corporation’s London operation. Finally it granted Elsinore, not Playboy, a license. The Playboy name was removed from the property in 1984. Elsinore renamed it the Atlantis.

Whatever the name was, the property had a lot going for it. Atlantis had a prime Boardwalk location, boasted 500 rooms, good restaurants, swinging lounges and a showroom that consistently booked name talent. The property marketed aggressively to the afternoon day-trippers, and booked afternoon shows in the cabaret, often featuring the likes of Frank Sinatra Jr. and Charlie Prose, specifically geared to the bus trade.

In my musician guise back then, I worked in the lounges of Playboy and Atlantis for several seasons, and can attest that the staff was just wonderful. They liked people and that’s something you don’t forget. Truthfully, having worked at most of the venues in operation at that time, Playboy/Atlantis was my favorite. Atlantis had a lot of devoted customers; there were just not enough of them.

Unfortunately, Atlantis wasn’t successful. In retrospect, it’s been said that the multi-level casino – as opposed to just one, gigantic, gaming floor – wasn’t particularly user friendly and that the property’s layout was confusing. One building housed the hotel rooms, restaurants and various levels of the casino, while the other building was home to the showroom and shops. Both were connected via skybridge. Note that it’s been said that the multi-level casino concept also contributed to the downfall of the Claridge as a casino, as well as the pre-Ocean Revel.

In 1985, Atlantis filed for bankruptcy, but continued to operate until 1989, when its gambling license was pulled. The casino closed in May, and less than one month later, Donald Trump swooped in to buy the property at a fire sale price of $63 million.

The Trump Regency operated until 1992, when ownership reverted to mortgage holder Chemical Bank. Trump bought it back in June of 1995, this time for $60 million, invested a reported $48 million to renovate it, and then reopened it again as Trump World’s Fair at Trump Plaza Hotel and Casino.

By then the whole enterprise was looked upon by hotel/casino experts as a white elephant. The hotel/casino continued to be troubled and simply couldn’t turn a profit. It closed for good on Oct. 3, 1999, and the building was torn down a year later.

The Playboy/Atlantis/Trump venue on the Boardwalk at Florida Avenue boasted several firsts: It was the first hotel and casino to have a female CEO, among the first to aggressively and successfully market to day-trippers, and sadly, was the first casino in Atlantic City to go out of business.

It wasn’t the last.

Bruce Klauber is the author of four books, an award-winning music journalist, concert and record producer and publicist, producer of the Warner Brothers and Hudson Music “Jazz Legends” film series, and performs both as a drummer and vocalist.